News is a tough mistress and journalists are but its one-night stands. Each dawn brings a new claimant to its affections and a new byline. Like a beautiful woman, it also plays hard to get, reveling in chase. “Milli (Found it)?” Short and stocky Purushottam, who haunted the corridors of Town Hall some two decades ago, would ask if I happened to run into him.

Did I ‘find it?’ Did I find ‘news?”

Purushottam was like a magpie that needed to carry off the brightest and the biggest chunk of ‘news’ from Town Hall, so that the next day, his prize may end up on the front page of the newspaper he worked for. Purushottam’s quest epitomizes the life of all journalists. You can find us in the shabby rooms of Shastri Bhawan, chatting up clerks and officers with the same aplomb. Or in the Home Ministry, trying to outsit the others in the OSD’s room in the hope of an ‘exclusive’ comment; under the blazing sun outside Parliament; fighting with cops for the right to enter a barricaded area strewn with blood and gore after a terrorist attack; or in the the shadows of booming guns in a battlefield, chasing that elusive news. When the day is winding down and the sun sinking into blissful sleep, we begin asking ourselves: “Milli?

A journalist learns early to pursue the big story that started out small. The need to connect the dots, to see where the ladder leads, even at the risk of getting swallowed by a snake, is a passion unlike any. In a journalist’s world, curiosity does not kill the cat. It creates a newshound.

Like the time I found myself staring at a young man pointing a stengun at me. The only other person in that deserted classroom was a shivering poll clerk, sitting in the teacher’s chair and stamping election ballots with shaking hands as the gunman hovered over his shoulders.

‘How many votes have been cast?” I asked the poll clerk, studiously ignoring the youth with the gun. Petrified with fear, the clerk said nothing and continued to furiously stamp the ballot papers one after another. I then looked at the goon standing inches away from me, his finger on the trigger. “Don’t you know it is illegal to bring firearms into a polling booth?” I said, sounding ridiculously schoolmarmish. Like the poll clerk, the goon didn’t say anything either. He gnashed his teeth and scowled back at me.

I could do nothing. After standing around for a couple of minutes, when stillness enveloped the room in a suffocating blanket, I left, feeling silly. I could have been shot for asking that absurdly rhetorical question: “Don’t you know it is illegal to bring firearms into a polling booth?” But I had to confront the crook. I couldn’t walk away, surrender meekly to a wrong. That was not what was expected of me in my job. That was not my training or my profession.

This was Meham, Haryana, in 1990 during a bloody by-election marked by blatant intimidation of voters. There was a huge crowd outside the school where the boothcapturing was on, but nobody wanted to mess with the Green Brigade, an army of gun-toting miscreants patronised by a state government desperate to retain power. A few kilometers away at Bainsi village, a similar drama was getting played out, but with a difference. The villagers had surrounded the school where Green Brigade hoodlums had captured a polling booth. There was a standoff between the villagers and the Haryana police who wanted to help the criminals, led by Abhay Singh Chautala, son of the then chief minister Om Prakash Chautala, escape. As I hurried towards the village, a Newstrack team stopped my car. “Don’t go there. The villagers are beating up reporters.”

A shameful rescue and a reminder that journalists can only tell a story. The rest depends on the system

There was no turning back. If there was news, I had to cover it. Photographer Kamal Narang and I were the only journalists to reach Bainsi village that day and what we saw shocked the entire nation. Nine villagers had been shot dead in a pitched battle with the police. We watched,as the politician’s son was escorted out of the school by cops under cover of gunfire. Kamal and I were sole witnesses to this shameful rescue, and the horrific killings of unarmed villagers. Our office car was used to take victims to hospital and one of them died on way. We had to hide till our car returned, covering ourselves in blankets given to us by villagers grateful to have allies against a brutal regime. National Herald, where I was chief reporter then, led with our exclusive coverage of the poll violence, ‘Mayhem in Meham.’ The uproar that followed forced the Congress to sack the chief minister and till this day, the headline of that story is used to sum up the complete subversion of democracy in Haryana during the elections in 1990.

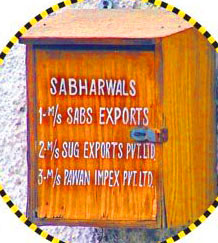

I didn’t go gunning for a big story in Meham. The big story was there and I found it, because as a reporter, I wouldn’t walk away from injustice. The same way I wouldn’t walk away when I saw the names of those three companies on a shabby letterbox outside Justice Sabharwal’s house two decades later. The defiance of that white paint on a brown letterbox, which stared at the world with the confidence that it would find no challenger, was entirely misplaced.

Next: Googly

To Be Continued